THE MIRROR OF LITERATURE, AMUSEMENT, AND INSTRUCTION.

| Vol. 10, No. 268.] | SATURDAY, AUGUST 11, 1827. | [PRICE 2d. |

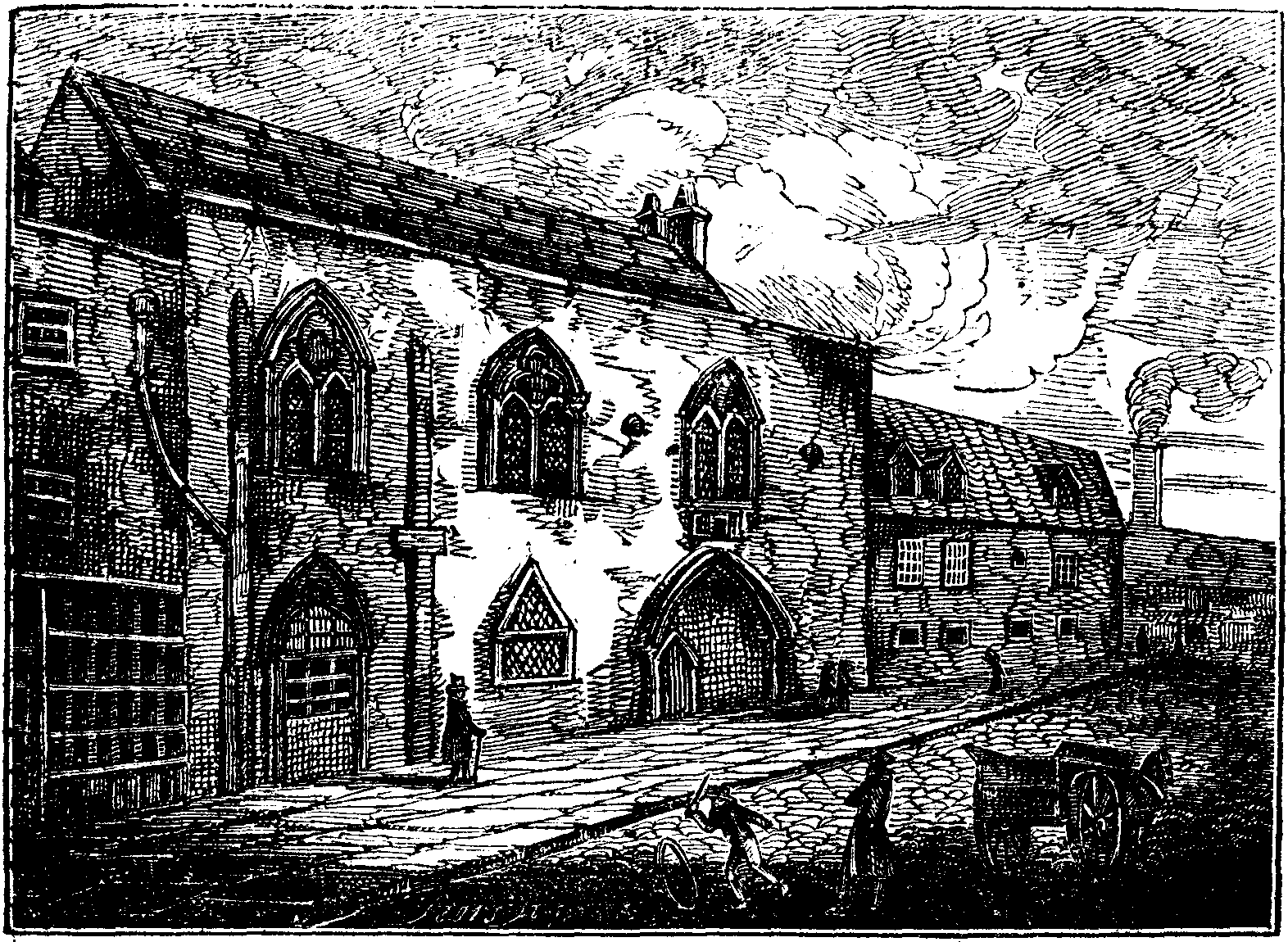

HOSPITAL OF ST. THOMAS, CANTERBURY.

The subject of the above engraving claims the attention of the antiquarian researcher, not as the lofty sculptured mansion of our monastic progenitors, or the towering castle of the feudatory baton, for never has the voice of boisterous revelry, or the tones of the solemn organ, echoed along its vaulted roof; a humbler but not less interesting trait marks its history. It was here that the zealous pilgrim, strong in bigot faith, rested his weary limbs, when the inspiring name of Becket led him from the rustic simplicity of his native home, to view the spot where Becket fell, and to murmur his pious supplication at the shrine of the murdered Saint; how often has his toil-worn frame been sheltered beneath that hospitable roof; imagination can even portray him entering the area of yon pointed arch, leaning on his slender staff—perhaps some wanderer from a foreign land.

The hospital of St. Thomas the Martyr of Eastbridge, is situated on the King's-bridge, in the hundred of Westgate, Canterbury, and was built by Becket, but for what purpose is unknown. However, after the assassination of its founder, the resort of individuals being constant to his shrine, the building was used for the lodgment of the pilgrims. For many years no especial statutes were enacted, nor any definite rules laid down for the treatment of pilgrims, till the see devolved to the jurisdiction of Stratford, who, in 15th Edward III. drew up certain ordinances, as also a code of regulations expressly to be acted on; he appointed a master in priest's orders, under whose guidance a secular chaplain officiated; it was also observed that every pilgrim in health should have but one night's lodging to the cost of fourpence; that applicants weak and infirm were to be preferred to those of sounder constitutions, and that women "upwards of forty" should attend to the bedding, and administer medicines to the sick.

This institution survived the general suppression of monasteries and buildings of its cast, during the reigns of Henry VIII. and the sixth Edward; and after alternately grading from the possession of private families to that of brothers belonging to the establishment, it was at last finally appropriated to the instruction of the rising generation, whose parents are exempt from giving any gratuity to the preceptor of their children.

Its present appearance is ancient, but not possessing any of those magic features which render the mansions of our majores so grand and magnificently solemn; a hall and chapel of imposing neatness and simplicity are still in good condition, but several of the apartments are dilapidated in part, and during a wet season admit the aqueous fluid through the chinks and fissures of their venerable walls.

SAGITTARIUS.

THE LECTURER.

MINOR AFFECTIONS OF THE BRAIN.

Pain in the head may arise from very different causes, and is variously seated. It has had a number of different appellations bestowed upon it, according to its particular character. I need not observe that headach is a general attendant of all inflammatory states of the brain, whether in the form of phrenitis, hydrocephalus acutus, or idiopathic fever; though with some exceptions in regard to all of them, as I before showed you. It is often also said to be a symptom of other diseases, of parts remotely situated; as of the stomach, more especially; whence the term sick headach, the stomach being supposed to be the part first or principally affected, and the headach symptomatic of this. I am confident, however, that in a majority of instances the reverse is the case, the affection of the head being the cause of the disorder of the stomach. It is no proof to the contrary, that vomiting often relieves the headach, for vomiting is capable of relieving a great number of other diseases, as well as those of the brain, upon the principle of counter-irritation. The stomach may be disordered by nauseating medicines, up to the degree of full vomiting, without any headach taking place; but the brain hardly ever suffers, either from injury or disease, without the stomach having its functions impaired, or in a greater or less degree disturbed: thus a blow on the head immediately produces vomiting; and, at the outset of various inflammatory affections of the brain, as fever and hydrocephalus, nausea and vomiting are almost never-failing symptoms. It is not denied, that headach may be produced through the medium of the stomach; but seldom, unless there is previously disease in the head, or at least a strong predisposition to it. In persons habitually subject to headach, the arteries of the brain become so irritable, that the slightest cause of disturbance, either mental or bodily, will suffice to bring on a paroxysm.

The occasional or exciting causes of headach, then, are principally these:—

- Emotions of mind, as fear, terror, and agitation of spirits; yet these will sometimes take off headach when present at the time.

- Whatever either increases or disorders the general circulation, and especially all causes that increase the action of the cerebral arteries, or, as it is usually though improperly expressed, which occasion a determination of blood to the head. Of the former kind are violent exercise, and external heat applied to the surface generally, as by a heated atmosphere or the hot bath; of the latter, the direct application of heat to the head; falls or blows, occasioning a shock to the brain; stooping; intense thinking; intoxicating drinks, and other narcotic substances. These last, however, as well as mental emotions, often relieve a paroxysm of headach, though they favour its return afterwards.

- A disordered state of the stomach, of which a vomiting of bile may be one symptom, is also to be ranked among the occasional causes of headach.

These occasional causes do not in general produce their effect, unless where a predisposition to the disease exists. This predisposition is often hereditary, or it may be acquired by long-protracted study and habits of intoxication.—Dr. Clutterbuck's Lectures on the Diseases of the Nervous System.

HYDROPHOBIA.

There is no cure for this disease when once the symptoms show themselves. A variety of remedies have from time to time been advertised by quacks. The "Ormskirk Medicine," at one time, was much in vogue; it had its day, but it did not cure the disease, nor, as far as I know, did it mitigate any of its symptoms. With regard to the affection of the mind itself in this disease, it does not appear that the patients are deprived of reason; some have merely, by the dint of resolution, conquered the dread of water, though they never could conquer the convulsive motions which the contact of liquids occasioned; while this resolution has been of no avail, for the convulsions and other symptoms increasing, have almost always destroyed the unhappy sufferers. —Abernethy's Lectures.

EFFECTS OF KINDNESS ON THE SICK.

DIET.

Experience has taught us that the nature of our food is not a matter of indifference to the respiratory organs. Diseased lungs are exasperated by a certain diet, and pacified by one of an opposite kind. The celebrated diver, Mr. Spalding, observed, that whenever he used a diet of animal food, or drank spirituous liquors, he consumed in a much shorter period the oxygen of the atmospheric air in his diving-bell; and he therefore, on such occasions, confined himself to vegetable diet. He also found the same effect to arise from the use of fermented liquors, and he accordingly restricted himself to the potation of simple water. The truth of these results is confirmed by the habits of the Indian pearl-divers, who always abstain from every alimentary stimulus previous to their descent into the ocean.—Dr. Paris on Diet.

THE MONTHS

The season has now advanced to full maturity. The corn is yielding to the sickle, the husbandmen,

"By whose tough labours, and rough hands,"

our barns are stored with grain, are at their toils, and when nature is despoiled of her riches and beauty, will, with glad and joyous heart, celebrate the annual festival of

THE HARVEST HOME.

BY CORNELIUS WEBBE.

Hark! the ripe and hoary rye

Waving white and billowy,

Gives a husky rustle, as

Fitful breezes fluttering pass.

See the brown and bending wheat,

By its posture seems to meet

The harvest's sickle, as it gleams

Like the crescent moon in streams,

Brown with shade and night that run

Under shores and forests dun.

Lusty Labour, with tired stoop,

Levels low, at every swoop,

Armfuls of ripe-coloured corn,

Yellow as the hair of morn;

And his helpers track him close,

Laying it in even rows,

On the furrow's stubbly ridge;

Nearer to the poppied hedge.

Some who tend on him that reaps

Fastest, pile it into heaps;

And the little gleaners follow

Them again, with whoop and halloo

When they find a hand of ears

More than falls to their compeers.

Ripening in the dog-star's ray,

Some, too early mown, doth lay;

Some in graceful shocks doth stand

Nodding farewell to the land

That did give it life and birth;

Some is borne, with shout and mirth,

Drooping o'er the groaning wain.

Through the deep embowered lane;

And the happy cottaged poor,

Hail it, as it glooms their door,

With a glad, unselfish cry,

Though they'll buy it bitterly.

And the old are in the sun,

Seeing that the work is done

As it was when age was young;

And the harvest song is sung;

And the quaint and jocund tale

Takes the stint-key from the ale,

And as free and fast it runs

As a June rill from the sun's

Dry and ever-drinking mouth:—

Mirth doth alway feel a drowth.

Butt and barrel ceaseless flow

Fast as cans can come and go;

One with emptied measures comes

Drumming them with tuneful thumbs;

One reels field-ward, not quite sober,

With two cans of ripe October,

Some of last year's brewing, kept

Till the corn of this is reaped.

Now 'tis eve, and done all labour,

And to merry pipe and tabor,

Or to some cracked viol strummed

With vile skill, or table drummed

To the tune of some brisk measure,

Wont to stir the pulse to pleasure,

Men and maidens timely beat

The ringing ground with frolic feet;

And the laugh and jest go round

Till all mirth in noise is drowned.

Literary Souvenir.

ARMORIAL BEARINGS AT CROYDON PALACE.

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

Sir,—In No. 266 of the Mirror, Sagittarius wishes to know the name of the person whose armorial bearings are emblazoned at Croydon palace.

From the blazon he has given, it is rather difficult to find out; but I should think they are meant for those of king Richard II. Impaled on the dexter side with those of his patron saint, Edward the Confessor. Bearings that may be seen in divers places at Westminster Hall, rebuilt by that monarch.1

I have subjoined the proper blazon of the arms, which is azure, a cross patonce between five martlets or, impaling France and England quarterly, 1st. and 4th. azure three fleurs de lis. 2nd. or, 2nd and 3rd Gules, 3 lions passant guardant in pale, or.

The supporting of the arms with angels, &c. was a favourite device of Richard, as may be seen in divers antiquarian and topographical works.

It is probable the hall of Croydon palace was built during the reign of Richard, which will account for his arms being placed there.

I am, &c.

C. F.

DEATH OF MR. CANNING.

The lamentable and sudden death of the Right Hon. George Canning has produced a general sensation throughout this country. At the opening of the present year our nation deplored the loss of a prince endeared to the people by his honest worth—but a short interval has elapsed and again the country is plunged in sorrow for the loss of one of its most zealous supporters—one of its chiefest ornaments—one of its staunchest friends—and one of its most eloquent and talented statesmen! The life of the late George Canning furnishes much matter for meditation and thought. From it much may be learnt. He was a genius, in the most unlimited sense of the word; and his intellectual endowments were commanding and imperative. Of humble origin he had to contend with innumerable difficulties, consequent to his station in life,—and although his talents, which were of the first order, befitted him for the first rank in society, that rank he did not attain until the scene of this world was about to be closed for ever from him. It may be said of this eminent man, that he owed nothing to patronage—his talents directed him to his elevated station, and to his intellectual superiority homage was made,—not to the man.

But, in other respects, the loss of Mr. Canning is a national bereavement. He was one of the master-spirits of the age. His very name was distinguished—for he has added to the literature of his country—by his writings and his eloquence he has stimulated the march of mind; he has seconded the exertions of liberal friends to the improvements of the uneducated, and he has patronized the useful as well as the fine arts, philosophy and science, of his country. To expatiate at greater length would be superfluous, as we have in another place recorded our humble tribute to his general character.2 We have now, therefore, merely to put together the melancholy facts connected with his death, and which will convey to another generation a just sense of the value, in our time, attached to a noble and exalted genius. The just and elegant laconism of Byron, by substituting the past for the present tense, may now be adopted as a faithful and brief summary of what was George Canning.

"Canning was a genius, almost an universal one:—an orator, a wit, a poet, and a statesman."

The king, with his usual quickness, was the first to perceive the dangerous state of Mr. Canning. We understand, that almost immediately after he had quitted him, on Monday, his majesty observed to sir William Knighton, that Mr. Canning appeared very unwell, and that he was in great alarm for him. On Tuesday, sir William repaired to town, at the express command of his majesty, to see Mr. Canning. At the interview with him, at the Treasury, Sir William made particular inquiries into the state of his health. Mr. Canning was then troubled with a cough, and he observed to Sir William that he almost felt as if he were an old man; that he was much weakened; but had no idea of there being anything dangerous in his condition, and that he trusted that rest and retirement would set him to rights. Sir William sent Dr. Maton to Mr. Canning, and on parting with him, he observed that, as he should not leave town until Wednesday morning, he would call on him, at Chiswick, on his way home to Windsor. Sir William found Mr. Canning in bed, at Chiswick. He asked him if he felt any pain in his side? Mr. Canning answered he had felt a pain in his side for some days, and on endeavouring to lie on his side, the pain was so acute that he was unable to do so. Sir William then inquired if he felt any pain in his shoulder? He said he had been for some time affected by rheumatic pains in the shoulder. Sir William told him that the pain did not arise from rheumatism, but from a diseased liver, and he immediately sent for the three physicians, who remained with him, and were to the last unremitting in their attentions.

The disease continued to make rapid progress, in spite of all that the first medical skill could do to baffle it, watching every turn it took, and applying, on the instant, every remedy likely to subdue its virulence, and mitigate his sufferings.

On the following Sunday, August 5, bulletins were issued, stating that Mr. Canning was in most imminent danger. The most painful interest was excited in the public mind by subsequent announcements of his alarming state, and on Wednesday morning, the following melancholy intelligence reached town:—

Chiswick, Wednesday, August, 8, 1827, (A. M.)

Mr. Canning expired this morning, without pain, at ten minutes before four o'clock.

MISCELLANIES.

BLACK BEARD.

There are few persons who reside on the Atlantic ocean and rivers of North America who are not familiar with the name of Black Beard, whom traditionary history represents as a pirate, who acquired immense wealth in his predatory voyages, and was accustomed to bury his treasures in the banks of creeks and rivers. For a period as low down as the American revolution, it was common for the ignorant and credulous to dig along these banks in search of hidden treasures; and impostors found an ample basis in these current rumours for schemes of delusion. Black Beard, though tradition says a great deal more of him than is true, was yet a real person, who acquired no small fame by his maritime exploits during the first part of the eighteenth century. Among many authentic and recorded particulars concerning him, the following account of his death may gratify curiosity:—

From the nature of Black Beard's position in a sloop of little draught of water, on a coast abounding with creeks, and remarkable for the number and intricacy of its shoals, with which he had made himself intimately acquainted, it was deemed impossible to approach him in vessels of any force. Two hired sloops were therefore manned from the Pearl and Lime frigates, in the Chesapeake, and put under the command of Lieutenant Maynard, with instructions to hunt down and destroy this pirate wherever he should be found. On the 17th of November, in the year 1718, this force sailed from James River, and in the evening of the 21st came to an inlet in North Carolina, where Black Beard was discovered at a distance, lying in wait for his prey. The sudden appearance of an enemy, preparing to attack him, occasioned some surprise; but his sloop mounting several guns, and being manned with twenty-five of his desperate followers, he determined to make a resolute defence; and, having prepared his vessel over night for action, sat down to his bottle, stimulating his spirits to that pitch of frenzy by which only he could rescue himself in a contest for his life. The navigation of the inlet was so difficult, that Maynard's sloops were repeatedly grounded in their approach, and the pirate, with his experience of the soundings, possessed considerable advantage in manoeuvring, which enabled him for some time to maintain a running fight. His vessel, however, in her turn, having at length grounded, and the close engagement becoming now inevitable, he reserved her guns to pour in a destructive fire on the sloops as they advanced to board him. This he so successfully executed, that twenty-nine men of Maynard's small number were either killed or wounded by the first broadside, and one of the sloops for a time disabled. But notwithstanding this severe loss, the lieutenant persevered in his resolution to grapple with his enemy, or perish in the attempt. Observing that his own sloop, which was still fit for action, drew more water than the pirate's, he ordered all her ballast to be thrown out, and, directing his men to conceal themselves between decks, took the helm in person, and steered directly aboard of his antagonist, who continued inextricably fixed on the shoal. This desperate wretch, previously aware of his danger, and determined never to expiate his crimes in the hands of justice, had posted one of his banditti, with a lighted match, over his powder-magazine, to blow up his vessel in the last extremity. Luckily in this design he was disappointed by his own ardour and want of circumspection; for, as Maynard approached, having begun the encounter at close quarters, by throwing upon his antagonist a number of hand-grenadoes of his own composition, which produced only a thick smoke, and conceiving that, from their destructive agency, the sloop's deck had, been completely cleared, he leaped over her bows, followed by twelve of his men, and advanced upon the lieutenant, who was the only person then in view; but the men instantly springing up to the relief of their commander, who was now furiously beset, and in imminent danger of his life, a violent contest ensued. Black Beard, after seeing the greater part of his men destroyed at his side, and receiving himself repeated wounds, at length, stepping back to cock, a pistol, fainted with the loss of blood, and expired on the spot. Maynard completed his victory, by securing the remainder of these desperate wretches, who were compelled to sue for mercy, and a short respite from a less honourable death at the hands of the executioner.

ISLANDS PRODUCED BY INSECTS.

The whole group of the Thousand Islands, and indeed the greater part of all those whose surfaces are flat, in the neighbourhood of the equator, owe their origin to the labours of that order of marine worms which Linnaeus has arranged under the name of Zoophyta. These little animals, in a most surprising manner, construct their calcareous habitations, under an infinite variety of forms, yet with that order and regularity, each after its own manner, which to the minute inquirer, is so discernable in every part of the creation. But, although the eye may be convinced of the fact, it is difficult for the human mind to conceive the possibility of insects so small being endued with the power, much less of being furnished in their own bodies with the materials of constructing the immense fabrics which, in almost every part of the Eastern and Pacific Oceans lying between the tropics, are met with in the shape of detached rocks, or reefs of great extent, just even with the surface, or islands already clothed with plants, whose bases are fixed at the bottom of the sea, several hundred feet in depth, where light and heat, so very essential to animal life, if not excluded, are sparingly received and feebly felt. Thousands of such rocks, and reefs, and islands, are known to exist in the eastern ocean, within, and even beyond, the limits of the tropics. The eastern coast of New Holland is almost wholly girt with reefs and islands of coral rock, rising perpendicularly from the bottom of the abyss. Captain Kent, of the Buffalo, speaking of a coral reef of many miles in extent, on the south-west coast of New Caledonia, observes, that "it is level with the water's edge, and towards the sea, as steep to as a wall of a house; that he sounded frequently within twice the ship's length of it with a line of one hundred and fifty fathoms, or nine hundred feet, without being able to reach the bottom." How wonderful, how inconceivable, that such stupendous fabrics should rise into existence from the silent but incessant, and almost imperceptible, labours of such insignificant worms!

To buy books, as some do who make no use of them, only because they were published by an eminent printer, is much as if a man should buy clothes that did not fit him, only because they were made by some famous tailor.—Pope.

TO MY BROTHER, ON HIS LEAVING ENGLAND.

By The Author of "Ahab."

(For the Mirror.)

Wherever your fortune may lead you to roam,

Forget not, young exile, the land of your home;

Let it ever be present to memory's eye,

'Tis the place where the bones of your fore-father's lie.

Let the thought of it ever your comforter be,

For no spot on this earth like your home can you see.

The fields where you rove may be more fresh and fair,

More splendid the sun, and more fragrant the air,

More lovely the flowers, more refreshing the breeze,

More tranquil the waters, more fruitful the trees.

But home after all things—that dear little spot,

Tho' it be but a desert can ne'er be forgot.

In the thoughts of the day, and the dreams of the night,

On your eyes like the kiss of your mother 'twill light,

Then the mist will disperse which long absence has spread.

And the paths you have trodden again you shall tread.

Then farewell, young exile, wherever you roam,

Oh! dear as your honour, your life, be your home.

J.H.S.

RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS.

ORDERS FOR HOUSEHOLD SERVANTS IN 1566.

Orders for Household Servantes; first deuised by John Haryngton, in the yeare 1566, and renewed by John Haryngton, sonne of the saide John, in the yeare 1592: The saide John, the sonne, being then high shrieve of the county of Somerset.

Imprimis, That no servant bee absent from praier, at morning or euening, without a lawfull excuse, to be alleged within one day after, vppon paine to forfeit for eury tyme 2d.

II. Item, That none swear any othe, vppon paine for every othe 1d.

III. Item, That no man leaue any doore open that he findeth shut, without theare bee cause, vppon paine for euery time 1d.

IV. Item, That none of the men be in bed, from our Lady-day to Michaelmas, after 6 of the clock in the morning; nor out of his bed after 10 of the clock at night; nor, from Michaemas till our Lady-day, in bed after 7 in the morning, nor out after 9 at night, without reasonable cause, on paine of 2d.

V. That no man's bed bee vnmade, nor fire or candle-box vnclean, after 8 of the clock in the morning, on paine of 1d.

VI. Item, That no one commit any nuisance within either of the courts, vppon paine of 1d.

VII. Item, That no man teach any of the children any vnhonest speeche, or evil word, or othe, on paine of 4d.

VIII. Item, That no man waite at the table without a trencher in his hand, except it be vppon some good cause, on paine of Id.

IX. Item, That no man appointed to waite at my table be absent that meale, without reasonable cause, on paine of 1d.

X. Item, If any man breake a glasse, hee shall aunswer the price thereof out of his wages; and, if it bee not known who breake it, the buttler shall pay for it on paine of 12d.

XI. Item, The table must bee couered halfe an houer before 11 at dinner, and 6 at supper, or before, on paine of 2d.

XII. Item, That meate bee readie at 11, or before, at dinner; and 6, or before, at supper, on paine of 6d.

XIII. Item, That none be absent, without leaue or good cause, the whole day, or any part of it, on paine of 4d.

XIV. Item, That no man strike his fellow, on paine of loss of seruice; nor reuile or threaten, or prouoke another to strike, on paine of 12d.

XV. Item, That no man come to the kitchen without reasonable cause, on paine of 1d. and the cook likewyse to forfeit 1d.

XVI. Item, That none toy with the maids, on paine of 4d.

XVII. That no man weare foule shirt on Sunday, nor broken hose or shooes, or dublett without buttons, on paine of 1d.

XVIII. Item, That, when any strainger goeth hence, the chamber be drest vp againe within 4 howrs after, on paine of 1d.

XIX. Item, That the hall bee made cleane euery day, by eight in the winter, and seauen in the sommer, on paine of him that should do it to forfeit 1d.

XX. That the cowrt-gate bee shutt each meale, and not opened during dinner and supper, without just cause, on paine the porter to forfet for euery time, 1d.

XXI. Item, That all stayrs in the house, and other rooms that neede shall require, bee made cleane on Fryday after dinner, on paine of forfeyture of euery on whome it shall belong vnto, 3d.

All which sommes shall be duly paide each quarter-day out of their wages, and bestowed on the poore, or other godly vse.

THE NOVELIST.

No. CVII.

THE WOOD KING.

By Miss Emma Roberts.

Already the pile of heaped-up fagots reached above the low roof of his hut; but Carl Scheffler still continued lopping off branches, and binding fresh bundles together, almost unconscious that the sun had set, and that the labours of the day being over, the neighbouring peasants were hastening to the skittle-ground to pass away an hour in sport. The wood-cutter's hut was perched upon an eminence a little out of the public path; but he heard the merry songs of his comrades as they proceeded gaily to the place of rendezvous, at the Golden Stag in the village below. Many of his intimate acquaintance paused as they approached the corner of the road nearest to his hut, and the wild wood rang with their loud halloes; but the call, which in other times had been echoed by the woodman's glad voice, was now unanswered; he busied himself with his work; his brow darkened as the joyous sounds came over his ear; he threw aside his hatchet, resumed, it again, and again casting it from him, exclaimed, "Why, let them go, I will not carry this chafed and wounded spirit to their revels; my hand is not steady enough for a bowling-match; and since Linda will doubtless choose a richer partner, I have no heart for the dance."

It was easy to perceive that Carl Scheffler was smarting under a recent disappointment: he had borne up bravely against the misfortunes which, from a state of comparative affluence, had reduced him to depend upon his own arm for subsistence, fondly trusting that ere long his prospects would amend; and that, at the return of the Count of Holberg to his ancestorial dominions, he should obtain a forester's place, and be enabled to claim the hand of Linda Von Kleist, to whom, in happier times, he had been betrothed. But these dreams had vanished; the count's bailiff having seen Linda, the flower of the hamlet, became his rival, and consequently his enemy: he had bestowed the office promised to Carl upon another; and Linda's father ungratefully withdrawing the consent given when the lover's affairs were in a more flourishing condition, had forbidden him the house. Buoyed up with the hope that Linda would remain faithful, and by her unabated attachment console him under the pressure of his calamities, Carl did not at first give way to despair; but Linda was too obedient, or perchance too indifferent, to disobey her father's commands. He sought her at the accustomed spot—she came not, sent not: he hovered round her residence, and if chance favoured him with a glimpse of his beloved, it was only to add to his misery, for she withdrew hastily from his sight. A rumour of the intended marriage of his perjured mistress reached his ears, and, struck to the soul, he endeavoured, by manual labour, to exhaust his strength and banish the recollection of his misery. He toiled all day in feverish desperation; and now that there was no more to be done, sat down to ponder over his altered prospects. The bailiff possessed the ear of his master, and it was useless to hope that the count would repair the injustice committed by so trusted a servant. The situation which above all others he had coveted, which would have given him the free range of the forest, the jovial hunter's life which suited his daring spirit, delighting in the perils of the chase, and, above all, a home for Linda, was lost, and for ever; henceforward he must relinquish all expectation of regaining the station which the misfortunes that had brought his parents to the grave had deprived him of, and be content to earn a sordid meal by bending his back to burthens befitting the brute creation alone; to hew wood, and to bear it to the neighbouring towns; to delve the ground at the bidding of a master, and to perform the offices of a menial hireling. "At least not here," cried the wretched young man, "not in the face of all my former friends; there is a refuge left where I may hide my sorrows and my wrongs. Fair earth, and thou fair sky, I gaze upon you for the last time; buried from the face of day in the centre of the deepest mine, I'll spend the remnant of my life unpitied and unknown." Determined to execute this resolution on the instant, Carl hastily collected such parts of his slender property as were portable; and having completed his arrangements, prepared to cross the Brocken, and shaped his course towards the Rammelsburg. The last rich gleam of crimson had faded from the sky; but there was light enough in the summer night to guide him on his way. A few bright and beautiful stars gemmed the wide concave of heaven; the air was soft and balmy, scarcely agitating the leaves of the forest trees; the fragrance-weeping limes gave out their richest scent, and the gentle gush of fountains, and the tricklings of the mountain springs, came in music on the ear; and had the traveller been more at ease, the calm and tranquil scene must have diffused its soothing influence over his heart. Carl, disregarding every thing save his own melancholy destiny, strode along almost choked by bitter thought, and so little heedful of the road, that he soon became involved in thickets whose paths were unknown to him; he looked up to the heavens, and shaping his course by one of the stars, was somewhat surprised to find himself still involved in the impenetrable mazes of the wood. Compelled to give more attention than heretofore to his route, he once or twice thought that he distinguished a human figure moving through the darkness of the forest. At first, not disposed to fall in with a companion, he remained silent, lest the person, whoever he might be, should choose to enter into conversation with him; then not quite certain whether he was right in his conjecture—for upon casting a second glance upon the object which attracted him, he more than once discovered it to be some stunted trunk or fantastic tree—he became anxious to ascertain whether he was in reality, alone, or if some other midnight wanderer trod the waste, and he looked narrowly around; all was still, silent, and solitary; and fancying that he had been deceived by the flitting shadows of the night, he was again relapsing into his former reverie, when he became aware of the presence of a man dressed in the garb of a forester, and having his cap wreathed with a garland of green leaves, who stood close at his side. Carl's tongue moved to utter a salutation, but the words stuck in his throat, an indescribable sensation of horror thrilled through his frame; tales of the demons of the Hartz rushed upon his memory—but he recovered instantly from the sudden shock. The desperate state of his fortune gave him courage, and, looking up, he was surprised at the consternation which the stranger had occasioned: he was a person of ordinary appearance, who, accosting him frankly, exclaimed, "Ho, comrade, thou art, I see, bent on the same errand as myself; but wherefore dost thou seek the treasures of the Nibelungen without the protecting wreath?"—"The treasures of the Nibelungen?" returned Carl; "I have indeed heard of such a thing, and that it was hidden in the bosom of the Hartz by a princess of the olden time; but I never was mad enough to think of so wild a chase as a search after riches, which has baffled the wisest of our ancestors, must surely prove."—"Belike then," replied the forester, "thou art well to do in the world, and therefore needest not to replenish thy wallets with gold,—travelling perchance to take possession of some rich inheritance."—"No, by St. Roelas," cried the woodcutter, "thou hast guessed wide of the mark. I am going to hide my poverty in the mine of Rammelsburg."—"The mine of Rammelsburg!" echoed the stranger, and laughed scornfully, so that the deep woods rang with the sound; and Carl feeling his old sensations return as the fiendish merriment resounded through the wilderness, again gazed stedfastly in his companion's face, but he read nothing there to justify his suspicions: the fiery eye lost its lustre; the lip its curl; and, gazing benignantly upon the forlorn wood-cutter, he continued his speech, saying, "Then prithee take the advice of one who knows these forests, and all that they contain. Here are materials in abundance for our garland; advance forward, and fear not the issue;"—and, gathering leaves from the boughs of trees of a species unknown to his new acquaintance, he twined them into a wreath, and placed the sylvan diadem on Carl's head. The instant that he felt the light pressure on his temples, all his fears vanished; and he followed his guide, conversing pleasantly through wide avenues and over broad glades of fresh turf, which seemed to be laid out like a royal chase, till they came to a wall of rock resembling the Hahnen Klippers, and entering through an arch, a grey moss-covered tower arose in the distance. The ponderous doors were wide open; and Carl advancing, found himself in a large hall well lighted, and showing abundance of treasure scattered abroad in all directions. He was conscious that he had lost his companion, but he seemed no longer to require his instruction; and casting down his own worthless burthen, he laded himself with the riches that courted his touch. The adventurer was soon supplied with a sufficient quantity of gold and jewels to satisfy his most unbounded wishes; and turning from the spot with a light heart, he sped merrily along. The country round about seemed strange to him; but on repassing the rocky ledge, a brisk wind suddenly springing up blew off his cap. The morning air was cold, and Carl, hastening to regain his head-gear, discovered that the wreath had disappeared; and, as if awakening from a dream, he found himself surrounded by familiar objects; he felt, however, the weight of the load upon his back, and though panting with the fatigue it occasioned, made the best of his way home. On approaching the hut, a low murmur struck on his ear. He paused; listened attentively; and distinguishing a female voice, he rushed forward, and in the next moment clasped Linda in his arms. She had fled from the persecutions of the bailiff to seek shelter in Carl's straw-roofed hut; and the now happy lovers, as they surveyed the treasures which had been snatched from the Nibelungen, agreed that they owed their good fortune to Riebezhahl the Wood King, who sometimes taking pity upon the frail and feeble denizens of earth, pointed out to their wondering eyes the inexhaustible riches of which he was the acknowledged guardian.

London Weekly Review.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS.

DRAFTS ON LA FITTE.

COOKE.

Only upon one occasion did Cooke deviate from his resolution of not apologizing to a provincial assembly, and that was at Liverpool. A previous breach of decorum was visited one night by the fury of an offended audience; confusion was at its height; the people were the actors, and Cooke the audience: yet the sturdy tragedian remained callous to the bursts of indignation which were heard around him, until destruction became the order of the day; lamps lighted on the stage; benches betokened mobility; pedal applications were made forté to the piano; basely violated was the repository of the base viol; and the property of poor Knight the manager gave every sign of that being its last appearance. What popular rage had failed to produce, consideration for the fortunes of his friend effected. At his entreaties, the Caledonian was induced to advance to the front of the stage (never was there a more moving scene than that before it); silence was obtained, and he condescended to express his sorrow for the state in which some nights previously he had presented himself: adding, "that he never before felt so keenly the degradation of his situation." Equivocal as was the mode of extenuation, the audience allied to Mersey accorded the mercy it possessed, and was or appeared to be, satisfied; but not so the actor, and he as fully as instantly avenged what he deemed his misplaced submission. As he concluded his address, he turned to the gratified but yet trembling manager, and (in allusion to the large share in the slave-trade then imputed to Liverpool) with that peculiarity of undertone he possessed, which could be distinctly heard throughout the largest theatre although pronounced as a whisper, exclaimed, "There's not a stone in the walls of Liverpool which has not been cemented by the bluid of Africans." Then, casting one of his Shylock glances of hatred and contempt on the mute and astounded audience, majestically left the stage.

On the first night of his performance at the Boston theatre, Richard was the part he had adopted; and so strongly had he fortified himself for the kingly task, that he deemed himself the very monarch he was destined to enact. The theatre was crowded in every part: expectation was on tiptoe: anticipation as to his person, voice, and manner, was announced by the sibilating "I guess" heard around, and "pretty considerable" agitation prevailed. The orchestra had begun and ceased, unheeded or unheard; nor could one of Sir Thomas Lethbridge's best cut and dried have produced less effect amongst the "irreclaimables." The curtain rose, and amidst thundering plaudits the welcome stranger advanced, in angles, to the front of the stage, and, as Sir Pertinax has it, "booed and booed and booed;" but greeting could not endure for ever: well justified curiosity assumed its station, and at length silence, almost breathless silence, reigned around, such as attended Irving in his Zoar, or Canning when he lately produced his budget. The hospitable clamour was over; but instead of "Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this sun of York" being given, Cooke, in a respectful but decided tone, requested that "God save the King" might be played by the orchestra prior to the commencement of the play. The proposal at first but excited mockery and laughter, which, however, gave way to far different feelings, on Cooke firmly and composedly declaring, that, until his request was complied with, he was determined not to proceed; and, should it be absolutely refused, he was resolved to retire. The fury of the Bostonians was at its height: menace, accompanied by every vituperative epithet rage could suggest, was lavished on the actor; but he kept his station, calm and secure as his own native island set in the stormy seas, until anger gradually subsided through very weariness; and every effort having been ineffectually used to wean "the tyrant" from his purpose, the political antipathies of the audience began to yield to their theatrical taste; and, after much argument and delay, the unpalatable demand was reluctantly assented to. Cooke, however, whose nature it was, when opposed, only to become more exigent, was not himself appeased; for, as the notes "unpleasing to a Yankee ear" were sounded, with a majestic wave of his hand he silenced the unwilling music, and, "Standing, if you please," was as dictatorially as fearlessly pronounced, to the consternation of the audience. So much had, however, already been accorded, that it was not deemed matter of much moment to concede the rest: and however ungracefully the attitude of respect was assumed, the national hymn was performed amidst grimace and muttering; Cooke beating time with his foot,—nodding significantly and satisfactorily at "Confound their politics;" and occasionally taking a pinch of snuff, as, in his royal robes, he triumphantly contemplated the astonished and indignant audience. It ended:—"Richard was himself again," and "Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer" was given with equal emphasis, feeling, and effect.

At the time that greater performer, the elephant, made his appearance on the boards, his own board became a subject of no trifling consideration with the managers, particularly as the African had taken a predilection for rum, which the new actor used to quaff with extraordinary zest. On one occasion Cooke was missing from a morning rehearsal, and all had been some time in waiting for the tragedian, when the messenger whom Kerable despatched in search of him, returned grinning to the green-room. "Where is Mr. Cooke, sir?" demanded Kemble. "He is below breakfasting with the elephant, sir!" was the reply.

It was too much for Cooke, after having so frequently disappointed full houses, to be obliged to play to an empty theatre. It was like playing whist with dummy. However, towards the close of the O. P. war, (which, by the way, excited more the attention of the Parisians than the national contest in which we were engaged,) the public had adopted the plan of never commencing operations until half-price, to the injury of the manager's purse. It was during the earlier acts of "The Man of the World," that Cooke, in performing to "a beggarly account of empty boxes," was addressed by one of the actors, in accordance with the scene, in a whisper; when the elevated comedian, casting a glance around, bitterly observed, "Speak out: there need be no secret. No one hears us." Poor Cooke could not plead in excuse what an actor did on being hissed for too sober a representation of a drunken part, "Ladies and gentlemen, I beg your pardon: but it is really the first time I ever was intoxicated."

His death was in singular accordance with his taste through life. He sought the banks of the Brandywine, and whether it were that the composition of its stream so little responded to its title as to prey upon his spirits, or from some other cause, there he "drank his last."

DICKEY SUETT.

I met with him once in a house situated on the very confines of Beef and Law; on the line of demarcation between the theatres and Lincoln's Inn; a sort of debateable ground between the spouters and ranters of the stage, and the eaters of commons, by either of which party it was frequented. Around a large table in the parlour sat a motley group. There were ragged wits, well-dressed students, new-fledged actors, a hackney writer or so, an Irish barrister named Shuter, a Scotch reporter, and a hodge-podge of most discordant materials congregated under the amalgamating power of Suett, who seemed, by the incongruity of his dress and diversified manner, to have studied the various tastes of those he swayed, and to be the comprehensive representative of each of the strange beings he looked upon, with all of whom he would occasionally identify himself with so much ease, that it were hard to say whether it was the result of labour or of tact, of calculation, or the mere impulse of mother-wit. The ropes of his face, when drawn taught, peculiarly commanded the attention of the Caledonian, while the sly and humorous glance of his half-shut eye was acknowledged by the Hibernian to whom it was addressed; the snow drift of powder which lay in patches on his long, straight hair, agreed with the taste of his dramatic nursling; the far-extended cambric of white frill imposed upon the students, while the unseemly rents in his coat at once compensated to the wits for what there might be of gaudy or gay in his outward man. We were received with equal courtesy and ceremony by the president; and were just seated, when a ballet-dancer of Drury-lane entered. As he was a Frenchman, it became a question of national politeness: and Dicky chestered him to his dexter! and, as was befitting, condescended to address him. "I am proud, sir," said Suett, with the formality of Black Rod himself, "to do the honours of my country to the representative of a nation which held my master Garrick in peculiar respect. He was a great actor, sir; a wonderful man! Your Lekain, or any other Cain, could not come up to him, for he was Able, Pardon the pun. Oh, la!—but he was vain, sir; vain as a peacock; it could not be of his person. Had he been, as Richard has it, 'a marvellous proper man' like myself, one might have said something. He used to say, I was too lean for Suett. Oh, dear. A votre santé, Monsieur, happy to see you on this side the Channel. Never been to France yet, although in the Straits great part of my life, and not unfrequently half seas over.—Well, sir, to return to Garrick. There was that man 'frae the north,' who wrote the History of England and Roderick Random,—the latter a true story, they say;—he who challenged Campbell the barrister, for calling him names, To bias the cause. Well, sir, Davy refused one of his farces; but the wily Caledonian pocketed the affront, in coolly observing, 'that he had nearly completed another volume of his history, and hoped he might be permitted to name the British Roscius, the pride of his country, and all that sort of thing.' It was a palpable hit, sir—the thing was settled—the manager managed; and Smelfungus retired, without his manuscript, half sorry he had not added another scene to his farce. Well, sir, the story got wind, and some days after Davy dined with a lawyer who had interested himself vainly for a friend's comedy with him, when, in the course of conversation, the barrister observed to Davy, before a large company, that he had nearly compiled another volume of The Statutes at large (would they were all at large), and hoped he might be permitted to name the British Roscius, the pride of his country. There was a roar at the expense of Garrick. 'The galled jade' winced terribly:—he was touchy as tinder, sir:—never was Digest so ill-digested.'"

It was when the meteor-like popularity of little Betty was at its height that poor Suett fell ill, at what he termed his town residence (a second-floor in a low street), and the pigmy Roscius, having eaten too much fruit, kept all London in intense agony for his fate at the same moment. Bulletins were exhibited in Southampton-row several times a-day, signed by numerous physicians. Had he died, how posterity would have been befooled! Suett was then actually dying, yet would he have his joke, and his last moments were cheered by the horse-laugh of the rabble assembled to spell the bulletin suspended to "the second-floor bell," attested by the mark of the old woman who attended him. "You shall be buried in Saint Paul's," said a friend. "Oh, la!" was the dying ejaculation of the comedian.

New Monthly Magazine.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS.

AMERICAN TRAVELLING.

June 7th, at three in the morning, the steam-boat (which was of immense size, and on the high pressure system) arrived at Albany, having come one hundred and sixty miles in seventeen hours, including stoppages. I found that, unluckily, the mail-coach had left the place just before our arrival, so I booked myself in an accommodation-stage, which was to reach Boston (a distance of one hundred and sixty miles) in three days, and entered the wretched-looking vehicle, with a heavy heart, at eight o'clock.... The machine in which I travelled was slow and crowded. The proprietor had undertaken to let us rest at night on the road; but we found that his notions of rest were very imperfect, and that his night was one of the polar regions.—Having partaken of a wretched dinner at Sand Lake, we arrived about one in the morning at Cheshire, where we were to sleep.

By dint of most active exertion, I secured a bed to myself, the narrow dimensions of which precluded the possibility of participation, and plunged into it with all possible haste, as there was not a moment to be lost. Secure in "single blessedness," I was incredibly amused at the compliments of nocturnal arrangement which passed around me among my Yankee companions. They were nine in number, and occupied by triplets the three other beds which the room contained. Whether it was with a view of preserving their linen unrumpled, or of enjoying greater space, I cannot tell; but certain it is, that they divested themselves of clothing to a degree not generally practised in Europe. A spirit of accommodation appeared to prevail; and it seemed to be a matter of indifference whether to occupy the lateral portions of the bed, or the warmer central position, except in one instance, where a gentleman protested against being placed next to the wall, as he was in the habit of chewing tobacco in his sleep!

At four o'clock in the morning we again set off, and, as much rain had fell in the night, the roads were in a dreadful state. The coach company now consisted of nine passengers inside, one on the top, (which, from its convex form, is a very precarious situation,) and three on the box, besides the coachman, who sat on the knees of the unfortunate middle man,—an uneasy burden, considering the intense heat of the weather.

It matters little to the American driver where he sits; he is indeed, in all respects, a far different personage from his great-coated prototype in England. He is in general extremely dexterous in the art of driving, though his costume is of a most grotesque description. Figure to yourself a slipshod sloven, dressed in a striped calico jacket and an old straw hat, alternately arranging the fragile harness of his horses, and springing again upon his box with surprising agility; careless of the bones of his passengers, and confident in his skill and resources, he scruples not frequently to gallop his coach over corderoy roads, (so called from being formed of the trunks of trees laid transversely,) or dash it round corners, and through holes that would appal the heart of the stoutest English coachman, however elated by gin, or irritated by opposition. I was once whirled along one of these roads, when the leathers, (barbarous substitutes for springs,) which supported the carriage gave way with a sudden shock. The undaunted driver instantly sprang from his box, tore a stake from a rail fence by the road-side, laid it across under the body of the coach, and was off again before I properly recovered the use of my senses, which were completely bewildered by the jolting I had undergone. I can compare it to nothing but the butt of Regulus, without the nails. When the lash and butt-end of the whip fail him, he does not scruple to use his foot, as the situation of his seat allows the application of it to his wheelers.

We dined at New Salem at six, and arrived at Petersham, where we were to sleep, at twelve o'clock at night, having been twenty hours coming sixty miles.

Though tired and disgusted with my journey, the prospect of a short respite from this state of purgatory was embittered during the last few miles by alarm at the idea of passing the night with one, if not two, of my fellow-travellers; and I internally resolved rather to sleep upon the floor.

After a desperate struggle, I succeeded, to my great joy, in securing a bed for myself, not, however, without undergoing a severe objurgation from the landlady, who could not understand such unaccommodating selfishness. Short were our slumbers. By the rigid order of the proprietor, we were turned out the next morning at three, and pursued our journey.—De Roos's Personal Narrative.

KANGAROO WAGGERY.

One of the largest tame kangaroos I have seen in the country is domiciled here, and a mischievous wag he is, creeping and snuffing cautiously toward a stranger, with such an innocently expressive countenance, that roguery could never be surmised to exist under it—when, having obtained as he thinks a sufficient introduction, he claps his forepaws on your shoulders, (as if to caress you,) and raising himself suddenly upon his tail, administers such a well-put push with his hind-legs, that it is two to one but he drives you heels over head! This is all done in what he considers facetious play, with a view to giving you a hint to examine your pockets, and see what bon-bons you have got for him, as he munches cakes and comfits with epicurean gout; and if the door be ajar, he will gravely take his station behind your chair at meal-time, like a lackey, giving you an admonitory kick every now and then, if you fail to help him as well as yourself.—Two Years in New South Wales.

A MAGNIFICENT WATERFALL.

My swarthy guides, although this was unquestionably the first time that they had ever led a traveller to view the remarkable scenery of their country, evinced a degree of tact, as ciceroni, as well as natural feeling of the picturesque, that equally pleased and surprised me. Having forewarned me that this was not yet the waterfall, they now pioneered the way for about a mile farther along the rocks, some of them keeping near, and continually cautioning me to look to my feet, as a single false step might precipitate me into the raging abyss of waters, the tumult of which seemed to shake even the solid rocks around us.

At length we halted, as before, and the next moment I was led to a projecting rock, where a scene burst upon me, far surpassing my most sanguine expectations. The whole water of the river (except what escapes by the subsidiary channel we had crossed, and by a similar one on the north side) being previously confined to a bed of scarcely one hundred feet in breadth, descends at once in a magnificent cascade of full four hundred feet in height. I stood upon a cliff nearly level with the top of the fall, and directly in front of it. The beams of the evening sun fell upon the cascade, and occasioned a most splendid rainbow; while the vapoury mists arising from the broken waters, the bright green woods that hung from the surrounding cliffs, the astounding roar of the waterfall, and the tumultuous boiling and whirling of the stream below, striving to escape along its deep, dark, and narrow, path, formed altogether a combination of beauty and grandeur, such as I never before witnessed. As I gazed on this stupendous stream, I felt as if in a dream. The sublimity of nature drowned all apprehensions of danger; and, after a short pause, I hastily left the spot where I stood to gain a nearer view from a cliff that impended over the foaming gulf. I had just reached this station, when I felt myself grasped all at once by four Korannas, who simultaneously seized hold of me by the arms and legs. My first impression was, that they were going to hurl me over the precipice; but it was a momentary thought, and it wronged the friendly savages. They are themselves a timid race, and they were alarmed, lest my temerity should lead me into danger. They hurried me back from the brink, and then explained their motive, and asked my forgiveness. I was not ungrateful for their care, though somewhat annoyed by their officiousness.—Thompson's Travels in Southern Africa.

SETTING IN OF AN INDIAN MONSOON.

The shades of evening approached as we reached the ground, and just as the encampment was completed the atmosphere grew suddenly dark, the heat became oppressive, and an unusual stillness presaged the immediate setting in of the monsoon. The whole appearance of nature resembled those solemn preludes to earthquakes and hurricanes in the West Indies, from which the east in general is providentially free. We were allowed very little time for conjecture; in a few minutes the heavy clouds burst over us.... I witnessed seventeen monsoons in India, but this exceeded them all in its awful appearance and dreadful effects.

Encamped in a low situation, on the borders of a lake formed to collect the surrounding water, we found ourselves in a few hours in a liquid plain. The tent-pins giving way, in a loose soil, the tents fell down, and left the whole army exposed to the contending elements.

It requires a lively imagination to conceive the situation of a hundred thousand human beings of every description, with more than two hundred thousand elephants, camels, horses, and oxen, suddenly overwhelmed by this dreadful storm, in a strange country, without any knowledge of high or low ground; the whole being covered by an immense lake, and surrounded by thick darkness, which prevented our distinguishing a single object, except such as the vivid glare of lightning displayed in horrible forms. No language can describe the wreck of a large encampment thus instantaneously destroyed and covered with water, amid the cries of old men and helpless women, terrified by the piercing shrieks of their expiring children, unable to afford them relief. During this dreadful night more than two hundred persons and three thousand cattle perished, and the morning dawn exhibited a shocking spectacle.—Forbes's Oriental Memoirs.

GRACE OF CARRIAGE.

This requires not only a perfect freedom of motion, but also a firmness of step, or constant steady bearing of the centre of gravity over the base. It is usually possessed by those who live in the country, and according to nature, as it is called, and who take much and varied exercise. What a contrast is there between the gait of the active mountaineer, rejoicing in the consciousness of perfect nature, and of the mechanic or shopkeeper, whose life is spent in the cell of his trade, and whose body soon receives a shape and air that correspond to this!—and in the softer sex, what a contrast is there, between her who recalls to us the fabled Diana of old, and that other, who has scarcely trodden but on smooth pavements or carpets, and who, under any new circumstances, carries her person as awkwardly as something to the management of which she is not accustomed.

Arnott's Elements of Physics.

THE CAVALRY SCHOOL OF ST. GERMAINS.

Bonaparte frequently visited the school of infantry at St. Cyr, reviewed the cadets, and gave them cold collations in the park. But he had never visited the school of cavalry since its establishment, of which we were very jealous, and did all in our power to attract him. Whenever he hunted, the cadets were in grand parade on the parterre, crying, "Vive l'Empereur!" with all their young energies; he held his hat raised as he passed them; but that was all we could gain. Wise people whispered that he never would go whilst they were so evidently expecting him; that he liked to keep them always on the alert; it was good for discipline. The general took another plan, and once allowed no sign of life about the castle when the emperor passed—it was like a deserted place. But it did not take neither; he passed, as if there were no castle there. It was desesperant. When, lo! the next day but one after I had spoken to him, he suddenly galloped into the court of the castle, and the cry of the sentinel, "L'Empereur!" was the first notice they had of it. He examined into every thing. All were in undress, all at work, and this was what he wanted. In the military-schools the cadets got ammunition-bread, and lived like well-fed soldiers; but there was great outcry in the circles of Paris against the bread of the school of St. Germain's. Ladies complained that their sons were poisoned by it; the emperor thought it was all nicety, and said no man was fit to be an officer who could not eat ammunition-bread. However, being there, he asked for a loaf, which was brought, and he saw it was villanous trash, composed of pease, beans, rye, potatoes, and every thing that would make flour or meal, instead of good brown wheaten flour. He tore the loaf in two in a rage, and dashed it against the wall, and there it stuck like a piece of mortar, to the great annoyance of those whose duty it was to have attended to this. He ordered the baker to be called, and made him look at it sticking. The man was in great terror first at the emperor's anger, but, taking heart, he begged his majesty not to take his contract from him, and he would give good bread in future; at which the emperor broke into a royal and imperial passion, and threatened to send him to the galleys; but, suddenly turning round, he said, "Yes, he would allow him to keep his contract, on condition that, as long as it lasted, he should furnish the school with good white household bread, (pain de ménage,) such as was sold in the bakers' shops in Paris; that he might choose that, or lose his contract;" and the baker thankfully promised to furnish good white bread in future, at the same price.—Appendix to the 9th volume of Scott's Life of Napoleon.